Where Did the Hebrews Go After Leaving This Promised Land (Likely Due to Famine)?

Moses (c. 1400 BCE) is considered one of the most important religious leaders in world history. He is claimed by the religions of Judaism, Christianity, Islam and Bahai as an important prophet of God and the founder of monotheistic belief.

The story of Moses is told in the biblical books of Exodus, Leviticus, Deuteronomy, and Numbers but he continues to be referenced throughout the Bible and is the prophet most often cited in the New Testament.

In the Quran he also plays an important role and, again, is the most often cited religious figure who is mentioned 115 times as opposed to Muhammed who is referred to by name only four times in the text. As in the Bible, in the Quran Moses is a figure who alternately stands for divine or human understanding.

Moses is best known from the story in the biblical Book of Exodus and Quran as the lawgiver who met God face-to-face on Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments after leading his people, the Hebrews, out of bondage in Egypt and to the "promised land" of Canaan. The story of the Hebrew Exodus from Egypt is only found in the Penteteuch, the first five books of the Bible, and in the Quran which was written later. No other ancient sources corroborate the story and no archaeological evidence supports it. This has led many scholars to conclude that Moses was a legendary figure and the Exodus story a cultural myth.

The Egyptian historian Manetho (3rd century BCE), however, tells the story of an Egyptian priest named Osarsiph who led a group of lepers in rebellion against the wishes of the king who wanted them banished. Osarsiph, Manetho claims, rejected the polytheism of Egyptian religion in favor of a monotheistic understanding and changed his name to Moses meaning "child of..." and usually used in conjunction with a god's name (Ramesses would be Ra-Moses, son of Ra, for example). Osarsiph would have attached no god's name to his own, it would seem, since he believed himself a son of a living god who had no name human beings could - or should - utter.

Moses could have been a mythological character who took on a life of his own as his story was told over & over again or could have been a real person to whom magical or supernatural events were ascribed or could have been precisely as he is depicted in the early books of the Bible & in the Quran.

Manetho's story of Osarsiph/Moses is related by the historian Flavius Josephus (c. 37-100 CE) who cited Manetho's story at length in his own work. The Roman historian Tacitus (c. 56-117 CE) tells a similar story of a man named Moses who becomes the leader of a colony of Egyptian lepers.

This has led a number of writers and scholars (Sigmund Freud and Joseph Campbell among them) to assert that the Moses of the Bible was not a Hebrew who was raised in an Egyptian palace but an Egyptian priest who led a religious revolution to establish monotheism. This theory links Moses closely with the pharaoh Akhenaten (1353-1336 BCE) who established his own monotheistic belief in the god Aten, unlike any other god and more powerful than all, in the fifth year of his reign.

Akhenaten's monotheism may have been born of a genuine religious impulse or could have been a reaction against the priests of the god Amun who had grown almost as wealthy and powerful as the throne. In establishing monotheism and banning all the old gods of Egypt, Akhenaten effectively eliminated any threat to the crown from the priesthood.

The theory advanced by Campbell and others (following Sigmund Freud's Moses and Monotheism in this) is that Moses was a priest of Akhenaten who led like-minded followers out of Egypt after Akhenaten's death when his son, Tutankhamun (c. 1336-1327 BCE), restored the old gods and practices. Still other scholars equate Moses with Akhenaten himself and see the Exodus story as a mythological rendering of Akhenaten's honest attempt at religious reform.

Moses is mentioned by a number of classical writers all drawing on the stories known in the Bible or by earlier writers. He could have been a mythological character who took on a life of his own as his story was told over and over again or could have been a real person to whom magical or supernatural events were ascribed or could have been precisely as he is depicted in the early books of the Bible and in the Quran.

Dating Moses' life and the precise date of the Exodus is difficult and is always based on interpretations of the Book of Exodus in conjunction with other books of the Bible and so are always speculative. It is entirely possible that the Exodus story was written by a Hebrew scribe living in Canaan who wished to make a clear distinction between his people and the older settlements of the Amorites in the region. The story of God's Chosen People led by his servant Moses to a land their God had promised them would have served this purpose well.

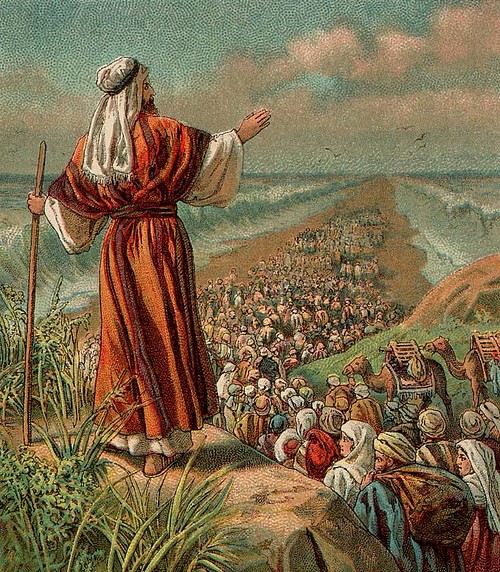

Moses Found by Pharaoh's Daughter

Providence Lithograph Company (Public Domain)

Moses in the Bible

The Book of Exodus (written c. 600 BCE) picks up from the narrative in the Book of Genesis (chapters 37-50) of Joseph, son of Jacob, who was sold into slavery by his jealous half-brothers and rose to prominence in Egypt. Joseph was adept at understanding dreams and interpreted the king's dream accurately predicting a coming famine. He was placed in charge of preparing Egypt for the famine, succeeded brilliantly, and brought his family to Egypt. The Book of Exodus opens with the Hebrew descendants of Joseph becoming more numerous in the land of Egypt so that the pharaoh, fearing they might seize power, enslaves them.

Moses enters the story in the second chapter of the book after the unnamed pharaoh, still worried about the growing population of the Israelites, decrees that every male child must be killed. Moses' mother hides him for three months but then, afraid he will be discovered and killed, places him in a papyrus basket, plastered with bitumen and pitch, and, with his sister watching over him, places it in the reeds by the Nile.

The basket floats down to where the pharaoh's daughter and her attendants are bathing and is discovered. The child is taken from the river by the princess who calls him "Moses" claiming she chose the name because she "drew him out of the water" (Exodus 2:10) which is making the assertion that "Moses" means "to draw out". This etymology of the name has been contested since, as noted, "Moses" in Egyptian meant "child of". Moses' sister, still watching over him, appears and suggests she bring a Hebrew woman to nurse the infant and so brings her mother who, initially at least, is reunited with her son.

Moses grows up in the Egyptian palace until one day he sees an Egyptian beating a Hebrew slave and kills him, burying his body in the sand. The next day, when he is again out among the people, he sees two Hebrews fighting and pulls them apart asking what the problem is. One of them answers by asking if he plans to kill them as he did the Egyptian. Moses then realizes his crime has become known and flees Egypt for Midian.

In the land of Midian he rescues the daughters of a high priest (named Reuel in Exodus 2 and Jethro afterwards) who gives him his daughter Zipporah as a wife. Moses lives in Midian as a shepherd until he one day encounters a bush which burns with fire but is not consumed. The fire is the angel of God who brings Moses a message that he should return to Egypt to free his people. Moses is not interested and bluntly tells God, "Please send someone else" (Exodus 4:13).

God is in no mood to be questioned on his choice and makes it clear that Moses will be returning to Egypt. He assures him all will be well and that he will have his brother, Aaron, to help him speak and supernatural powers which will enable him to convince pharaoh that he speaks for God. He also tells Moses, in a passage which has long troubled interpreters of the book, that he will "harden pharaoh's heart" against receiving the message and letting the people go at the same time that he wants pharaoh to accept the message and release his people.

Moses & The Seventh Plague of Egypt

John Martin (Public Domain)

Moses returns to Egypt and, as God had promised, pharaoh's heart is hardened against him. Moses and Aaron compete with the Egyptian priests in an effort to show whose god is greater but pharaoh is unimpressed. After a series of ten plagues destroys the land, finally killing the first-born of the Egyptians, the Hebrews are allowed to leave and, as God directed, they take a vast amount of treasure out of Egypt with them.

Pharaoh changes his mind after they have gone, however, and sends his army of chariots in pursuit. In one of the best-known passages from the Bible, Moses parts the Red Sea so his people can cross and then closes the waters over the pursuing Egyptian army, drowning them. He leads his people on, following two signs God provides: a pillar of cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. At Mount Sinai, Moses leaves his people below to ascend and meet God face to face; here he receives the Ten Commandments, God's laws for his people.

On the mountain, Moses receives the law and also instructions for the ark of the covenant and tabernacle which will house God's presence among the people. Down below, his followers have begun to fear him dead and, feeling hopeless, ask Aaron to make them an idol they can worship and ask for help. Aaron melts the treasures they took from Egypt in a fire to create a golden calf. On the mountain, God sees what the Hebrews are doing and tells Moses to return and deal with his people.

When he comes back down the mountain and sees his people worshipping the idol he becomes enraged and destroys the tablets of the Ten Commandments. He calls all who remained faithful to God to his side, including Aaron, and commands they kill their neighbors, friends, and brothers who forced Aaron to make the idol for them. Exodus 32:27-28 describes the scene and claims "about three thousand people" were killed by Moses' Levites. Afterwards, God tells Moses he will not accompany the people anymore because they are "stiff-necked people" and, should he travel further with them, he would wind up killing them out of frustration.

Moses and the elders then enter into a covenant with God by which he will be their only god and they will be his chosen people. He will travel with them personally as a divine presence to direct and comfort them. God writes the Ten Commandments on new tablets which Moses cuts for him and these are placed in the ark of the covenant and the ark is housed in the tabernacle, an elaborate tent.

God further commands that a lampstand of pure gold and a table of acacia wood be made and placed before his presence in the tabernacle for receiving offerings, specifies a courtyard to be created for the tabernacle, and outlines acceptable offerings and various sins one must avoid and atone for. No longer will the people have to question his existence or wonder what he wants because, between the Ten Commandments and the other instructions, everything is quite clear and, further, they will know he is among them in the tabernacle.

Even with God in their midst, however, the people still doubt and still fear and still question and so it is decreed that this generation will wander in the desert until they die; the next generation will be the one to see the promised land. Moses then leads his people through the desert for forty years until this is accomplished and the younger generation reaches the promised land of Canaan. Moses himself is not allowed to enter, only to look upon it from across the River Jordan. He dies and is buried in an unmarked grave on Mount Nebo and leadership is assumed by his second-in-command, Joshua son of Nun.

Moses' trials and challenges mediating between his people and God, as well as his laws, are given in the books of Numbers, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy which, taken with Genesis and Exodus, make up the first five books of the Bible, which traditionally are ascribed to Moses himself as author.

The Exodus story resonates as it does because it touches on universal themes & symbols regarding personal identity, purpose in life, & the involvement of the divine in human affairs.

The Hero's Story

Biblical scholarship, however, discounts Moses' authorship and maintains that the first five books were written by different scribes at different time periods. The story of Moses as related in Exodus is the hero's story as elaborated by Joseph Campbell in works such as The Hero with a Thousand Faces or Transformations of Myth Through Time.

Although Moses is born a Hebrew he is separated from his people shortly after birth and denied his cultural heritage. Upon discovering who he is he must leave the life of comfort he has grown used to and embarks on a journey which leads to his recognition of his purpose in life. He is afraid to accept what he knows he must do but does it anyway and succeeds. The Exodus story resonates as it does because it touches on universal themes and symbols regarding personal identity, purpose in life, and the involvement of the divine in human affairs.

Moses' entrance to the story purposefully employs the motif of the infant born of humble parents who becomes (or is unknowingly) a prince. At the time of the writing of Exodus this story had been known in the Middle and Near East for almost 2,000 years through the Legend of Sargon of Akkad. Sargon (2334-2279 BCE) was the founder of the Akkadian empire, the first multi-national empire in the world.

His famous legend, which he made great use of in his lifetime to achieve his aims, relates how his mother was a priestess who "set me in a basket of rushes and sealed my lid with bitumen/ She cast me into the river which rose over me. The river bore me up and carried me to Akki, the drawer of water. Akki, the drawer of water, took me as his son and reared me. Akki/the drawer of water, appointed me as his gardener" (Pritchard, 85-86). Sargon grows up to overthrow the king and unite the region of Mesopotamia under his rule.

Akkadian Ruler

Sumerophile (Public Domain)

Scholar Paul Kriwaczek, writing on Sargon's story, mentions the International Babylon Festival of 1990 CE at which Saddam Hussein celebrated his birthday. Kriwaczek writes:

The festivities came to a climax when a wooden cabin was wheeled out and large crowds dressed in ancient Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian costume prostrated themselves in front of it. The doors opened to reveal a palm tree from which fifty-three white doves flew up into the sky. Beneath them a baby Saddam, reposing in a basket, came floating down a marsh-bordered stream. Time magazine's reporter was particularly struck by the baby-in-the-basket theme, describing it as "Moses redux". But why on earth would Saddam Hussein wish to compare himself to a leader of the Jews? The journalist was missing the point. The motif was a Mesopotamian invention long before the Hebrews took it up and applied it to Moses. The Iraqi dictator was alluding to a much more ancient and, to him, far more glorious precedent. He was associating himself with Sargon. (112)

The writer of Exodus also wanted his hero associated with Sargon: a true hero who would rise from inauspicious beginnings to achieve greatness. Those who believe the Exodus story is a cultural myth point to Moses' beginnings, along with many other facets of the story, to prove their claim. Other scholars, such as Rosalie David or Susan Wise Bauer, accept the Exodus story as authentic history and ascribe to the characters in the story a knowledge of Sargon's legend which the author of Exodus faithfully set down. Bauer writes:

Sargon's birth story served as a seal of chosenness, a proof of his divinity. Surely the mother of the Hebrew baby knew it, and made use of it in a desperate (and successful) attempt to place her own baby in the line of the divinely chosen. (235-236)

Pharaoh, Victim of the 10th Plague of Egypt

James Jacques Joseph Tissot (Public Domain)

To these scholars the fact that there are no records of the Exodus and no archaeological evidence to support it can be explained by the embarrassment the departure of the Israelites would have caused the pharaoh of Egypt. Bauer writes:

The exodus of the Hebrews was a nose-thumbing directed not just at the power of the pharaoh and his court but at the power of the Egyptian gods themselves. The plagues were designed to ram home the impotence of the Egyptian pantheon. The Nile, the bloodstream of Osiris and the lifeblood of Egypt, was turned to blood and became foul and poisonous; frogs, sacred to Osiris, appeared in numbers so great that they were transformed into a pestilence; the sun-disk was blotted out by darkness. Ra and Aten both made helpless. These are not the kinds of events that appear in the celebratory inscriptions of any pharaoh. (236)

Exodus as History Theory

A simpler explanation, however, is that the events described in the Book of Exodus did not take place - or, at least, not as described - and so no inscriptions were made relating to them. The Egyptians are famous for their record-keeping and yet no records have been found which make the slightest reference to the departure of a segment of the population of the land which, according to the Book of Exodus, numbered "six hundred thousand men on foot besides women and children" (12:37) or, as given in Exodus 38:26, "everyone who had crossed over to those counted, twenty years old or more, a total of 603,550 men" again not counting women or children.

Even if the Egyptians decided the embarrassment of their gods and king was too great a shame to set down, some record would exist of such a huge movement of so vast a population even if that record were simply a dramatic change in the physical evidence of the region. There are seasonal camps from the Paleolithic Age in Scotland and other areas dating to c. 12,000 BCE (such as Howburn Farm) and these sites were not in use anywhere near the amount of time of the forty years of campsites the Hebrews would have made use of in their trip to the promised land.

Arguments by Egyptologists such as David Rohl, that evidence of the Exodus does exist, are not widely accepted by scholars, historians, or other Egyptologists. Rohl's claim is that one can find no physical or literary evidence of the Exodus only because one is looking in the wrong era. The Exodus has traditionally been placed in the reign of Ramesses II (1279-1213 BCE) but Rohl claims the events actually took place much earlier in the reign of the king Dudimose I (c. 1650 BCE). If one examines the evidence from that time, Rohl claims, the biblical narrative matches up with Egyptian history.

Moses & the Parting of the Red Sea

Providence Lithograph Company (Public Domain)

The problems with Rohl's theory are that it the evidence from the period of the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) and Second Intermediate Period (c. 1782-c. 1570 BCE) does not actually substantiate the Exodus story. The Ipuwer Papyrus, which Rohl claims is an Egyptian account of the Ten Plagues, is dated to the Middle Kingdom, long before Dudimose I's reign and, further, is quite clearly Egyptian literature of a known genre, not history.

The Semites Rohl asserts lived in great numbers at Avaris cannot be identified with the Israelites. In every instance where Rohl makes his claims linking the Book of Exodus with Egyptian history he either ignores details which prove him wrong or twists evidence to fit with his theory. In spite of Rohl's claims, and those of others who have seized on them, there is no archaeological or literary evidence of Moses leading the Israelites from slavery in Egypt. The only source for the story is the biblical narrative.

The Egyptian Priest Theory

Still, there is an Egyptian record of an event which, some claim, inspired the Exodus story in Manetho's account of the Egyptian priest Osarsiph and his leadership of the community of lepers. Manetho's account has been lost but is quoted at length by Josephus and later by the Roman historian Tacitus. According to Josephus, the king Amenophis of Egypt (who is equated with Amenhotep III, c. 1386-1353 BCE) wished to "see the gods" but was told by an oracle that he could not - unless he cleansed Egypt of lepers.

He therefore banished the lepers to the city of Avaris where they were united under the leadership of a monotheistic priest named Osarsiph. Osarsiph rebelled against the rule of Amenophis, instituted monotheism, and invited the Hyksos back into Egypt. In Tacitus' version, the Egyptian king is named Bocchoris (the Greek name for the king Bakenranef, c. 725-720 BCE) and he exiles a segment of his population afflicted with leprosy to the desert.

The exiles remain in the desert "in a stupour of grief" until one of them, Moses, rallies and leads them to another land. Tacitus goes on to say how Moses then taught the people a new belief in one supreme god and "gave them a novel form of worship, opposed to all that is practiced by other men" (1).

As with the Exodus story, there are no records which corroborate this version of events and the reign of Amenhotep III was not marked by any rebellions by lepers or anyone else. Tacitus' account of Moses coming to power during the reign of Bakenranef is equally unsupported. Further, Manetho's account explicitly states that Osarsiph "invited the Hyksos back into Egypt" where they ruled for thirteen years but the Hyksos were expelled from Egypt in c. 1570 BCE by Ahmose I of Thebes and no records indicate they ever returned.

Pharaoh Akhenaten, Cairo Museum

John Bodsworth (CC BY)

Historian Marc van de Mieroop comments on this, writing, "Scholars have different opinions about exactly what historical events Josephus's account recalls, but many see a lingering memory of Akhenaten and his unpopular rule in the tale" (210). Akhenaten famously introduced monotheism to Egypt through the worship of the one god Aten and proscribed the worship of all other gods. According to the theory most famously expounded by Freud, the Osarsiph story is actually an account of Akhenaten's reign and one of his priests, Moses, who carried on his reform.

Freud is openly bewildered by the fact that no one seems to have noticed that this allegedly Hebrew leader of the Exodus from Egypt had an Egyptian name, writing, "It might have been expected that one of the many authors who recognized Moses to be an Egyptian name would have drawn the conclusion, or at least considered the possibility, that the bearer of an Egyptian name was himself an Egyptian" (5-6). Freud further states:

I venture now to draw the following conclusion: if Moses was an Egyptian and if he transmitted to the Jews his own religion, then it was that of Ikhnaton [Akhenaten), the Aten religion. (27)

According to Freud, Moses was murdered by his people and the memory of this act created a communal guilt which infused the religion of Judaism and characterizes that belief system as well as those monotheistic faiths which came after it. As interesting as the theory may be, like many of Freud's theories, it is based on an assumption which Freud never proves but continues to build an argument on anyway. Susan Wise Bauer writes:

For at least a century, the theory that Akhenaten trained Moses in monotheism and then set him loose in the desert has floated around; it still pops up occasionally on History Channel specials and PBS fund raisers. This has absolutely no historical basis and in fact is incredibly difficult to square with any of the more respectable dates of the Exodus. It seems to have originated with Freud who was certainly not an unbiased scholar in his desire to explain the origins of monotheism while denying Judaism as much uniqueness as possible. (237)

Although his name certainly suggests an Egyptian origin, the first text which introduces the character of Moses clearly indicates he was the son of Hebrew parents. Whether one accepts the Book of Exodus as a reliable account or a cultural myth, one cannot change the text to fit one's personal theories which is basically what Freud does.

At the same time, one cannot claim a "respectable date" for the Exodus when there is no historical record of the event outside of the manuscript of the Book of Exodus. The events of the Exodus are traditionally assigned to the reign of Ramesses II based on the passage from Exodus 1:11 where it states that the Hebrew slaves worked on the cities of Pithom and Rameses, two cities Ramesses II was known to have commissioned.

Bauer, however, writes that a "respectable date" for the Exodus is 1446 BCE based on "a straightforward reading of I Kings 6:1 which claims that 480 years passed between the Exodus and the building of Solomon's temple" (236). Further complicating the dating of the event is that Exodus 7:7 states that Moses was 80 years old when he first met with pharaoh but Moses' birthdate is given by Rabbinical Judaism as 1391 BCE making the 1446 BCE date impossible and there are plenty of other suggestions for possible birth years as well which also make the 1446 BCE date for the Exodus untenable.

Exodus as Naru Literature

The problem with all these speculations stems from the attempt at reading the Bible as straight history instead of what it is: literature and, specifically, scripture. Ancient writers were not as concerned with facts as modern audiences are but were certainly interested in truth. This is exemplified by the ancient genre known as Mesopotamian Naru Literature in which a figure, usually someone famous, plays an important role in a story which they did not actually participate in.

The best examples of Naru Literature concern Sargon of Akkad and his grandson Naram-Sin (2262-2224 BCE). In the famous story "The Curse of Akkad", Naram-Sin is portrayed as destroying the temple of the god Enlil when he receives no answer to his prayers. There is no record of Naram-Sin doing any such thing while there is a great deal of evidence that he was a pious king who honored Enlil and the other gods. In this case, Naram-Sin would have been chosen as main character because of his famous name and used to convey a truth about humanity's relationship with the gods and, especially, a king's proper attitude toward the divine.

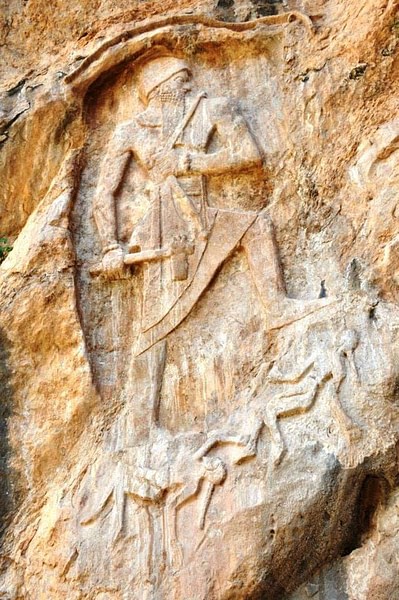

Naram-Sin Rock Relief, Sulaimaniya, Iraq

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin (Copyright)

In the same way, the Book of Exodus and the other narratives concerning Moses tell a story of physical and spiritual liberation using the central character of Moses - a figure previously unknown in literature - who represents man's relationship with God. The writers of the biblical narratives go to great lengths to ground their stories in history, to show God working through actual events, in the same way the authors of Mesopotamian Naru Literature chose historical figures to convey their message.

Literature, scripture, does not need to be historically accurate to express a truth. Insistence on stories such as the Book of Exodus as historical denies a reader a wider experience of the text. To claim that the book must be historically true to be meaningful denies the power of the story to relay its message.

Moses is a symbolic figure in the story while at the same time remaining a completely autonomous individual with a distinct personality. Throughout the narrative Moses mediates between God and the people but is neither completely holy nor secular. He accepts his mandate from God reluctantly, constantly asks God why he was chosen and what he is supposed to be doing, and yet consistently tries to do God's will until he strikes the stone to produce water instead of speaking to it as God had instructed (Numbers 20:1-12).

God had previously told Moses to strike a rock to get water (Exodus 17:6) but this time told him to speak to the rock. Moses' actions here, ignoring God's instruction, prevent him from entering the promised land of Canaan. He is allowed to see the land from Mount Nebo but cannot lead his people once he has compromised his relationship with God.

Moses Receives the 10 Commandments

Gebhard Fugel (Public Domain)

As with the rest of the narrative concerning Moses, this episode with the rock would have conveyed (still conveys) an important message about a believer's relationship with God: that one must trust in the divine in spite of one's own perceived knowledge or reliance on precedent and experience. It does not finally matter whether a historical individual named Moses struck or spoke to a rock which then gave water; what matters is the truth of the individual's relationship with God that story conveys and how one can better understand one's own place in a divine plan.

Moses in the Quran

This is also seen in the Quran where Moses is known as Musa. Musa is mentioned a number of times throughout the Quran as a righteous man, a prophet, and a sage. In the story of the Exodus in the Quran, Musa is always seen as a devout servant of Allah trusting in divine wisdom. In Surah 18: 60-82, however, a story is related which shows how even a great and righteous man still has much to learn from God.

One day, after Musa has delivered a particularly brilliant sermon, a member of the audience asks him if there is another on earth as learned in God's ways as he is and Musa answers no. God (Allah) informs him that there will always be those who know more than one does in anything, especially regarding the divine. Musa asks Allah where he might find such a man and Allah gives him instructions on how to proceed.

Following Allah's guidance, Musa finds Al-Khidr (a representative of the divine) and asks if he might follow him and learn all the knowledge he has of God. Al-Khidr answers that Musa would not understand anything he said or did and would have no patience; he then dismisses him. Musa pleads with him and Al-Khidr says, "If you would follow me, ask me not about anything until I mention it myself" and Musa agrees.

As with the biblical Moses, the Musa of the Quran is a completely developed character with all the strengths & weaknesses of any person.

As they travel together, Al-Khidr comes across a boat by the shore and kicks a hole in the bottom of it. Musa objects, crying out that the owners of the boat will not be able to earn their living now. Al-Khidr reminds him how he told him he could not be patient and dismisses him but Musa asks forgiveness and promises he will not judge or speak on anything else.

Shortly after the boat incident, though, they meet a young man on the road and Al-Khidr kills him. Musa strongly objects asking why such a handsome young man should be killed and Al-Khidr again reminds him of what he said before and tells him to leave now immediately. Musa again apologizes and is forgiven and the two travel on together.

They reach a town where they ask for alms but are refused. On their way out of the town they pass a stone wall which is falling down and Al-Khidr stops and repairs it. Musa is again confused and complains to his companion that at least he could have asked for wages in repairing the wall so they could get something to eat.

At this, Al-Khidr tells Musa that he has breached their contract for the last time and now they must part ways. First, though, he explains: he scuttled the boat because there was a king at sea seizing every boat which put out by force and enslaving the crew. If the good people who owned the boat had gone out, they would have met with a bad end. He killed the young man because he was evil and was going to bring great pain to his parents and community. Allah had already provided for another son to be born to the parents who would bring them and others joy instead of pain. He rebuilt the wall because there was a treasure hidden beneath it which two orphans were supposed to inherit and, if the wall had crumbled any more, it would have been revealed to those who would take it. Al-Khidr ends by saying, "That is the interpretation of those things over which you showed no patience" and Musa understands the lesson.

As with the biblical Moses, the Musa of the Quran is a completely developed character with all the strengths and weaknesses of any person. In the Bible, Moses' humility is emphasized but he still has enough pride to trust in his own judgment in striking the rock rather than in listening to God. In the Quran his faith in himself and his own perceptions and judgments is questioned through his inability to trust in God's messenger. The story from Surah 18 teaches that God has a purpose which human beings, even one as devout and learned as Musa, cannot understand.

Conclusion

Throughout the Christian New Testament Moses is cited more than any other Old Testament prophet or figure. Moses is seen as the Law Giver in the Christian writings who exemplifies a man of God. To cite only one example, Moses features prominently in the famous story Jesus tells concerning Lazarus and the Rich Man in Luke 16: 19-31.

In this story a poor, but pious, man named Lazarus and a rich man (unnamed) live in the same town. Lazarus suffers daily while the rich man has everything he could desire. They both die on the same day and the rich man wakes up in the underworld and sees Lazarus with Father Abraham in paradise. He begs Father Abraham to help him but is reminded that, on earth, he lived a life of ease while Lazarus suffered and now it is only just that the roles are reversed.

The rich man then asks Father Abraham to send someone to warn his family, as he has five brothers still living, and tell them how they should better live to avoid his fate. Abraham responds, "They have Moses and the prophets, let them listen to them." The rich man protests saying that if someone should rise from the dead to warn his family then they would surely listen but Abraham says, "If they will not listen to Moses and the prophets neither would they listen should someone rise from the dead."

In this story Moses is presented as the paradigm of God's truth. If people would heed Moses' example and words then they could avoid separation from God in the afterlife. The story emphasizes how Moses' teachings provide everything anyone needs to know about how to live a good and decent life and enjoy an afterlife with God and how, if one is going to ignore Moses and the prophets and justify one's life choices, one would just as easily dismiss someone returning from the dead; the two are equally self-evident of God's desires for human piety and behavior.

Moses is also featured in Jesus' transfiguation in Matthew 17:1-3, Mark 9:2-4, and Luke 9:28-30 along with Elijah when God announces that Jesus is his son with whom he is well pleased. In these passages and others in the New Testament Moses is held up as an exemplar and representative of God's will.

Whether there was a religious leader in history named Moses who led his people and initiated a monotheistic understanding of the divine is unknown. Individual beliefs will dictate whether one accepts the historicity of Moses or regards him as a mythical figure more than any historical evidence - or the lack of it - ever will. Either way, the figure of Moses has cast a long shadow across the history of the world.

The monotheism he is credited with introducing was further developed by the teachers of the Jewish faith which influenced the atmosphere in which Christianity was able to thrive which then led to the rise of Islam. All three major monotheistic religions in the world today claim Moses as their own and he continues to serve as a model of humanity's relationship with the divine for people of many faiths around the world.

Did you like this definition?

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Where Did the Hebrews Go After Leaving This Promised Land (Likely Due to Famine)?

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/Moses/